VitrinaLab Foundation presents

IVAN navarro

Nov 30th to Dec 5th

15 NE 41ST ST, DESIGN DISTRICT (NEXT TO DE LA CRUZ COLLECTION) MIAMI FL

Installation

Iván Navarro: The Fight Continues

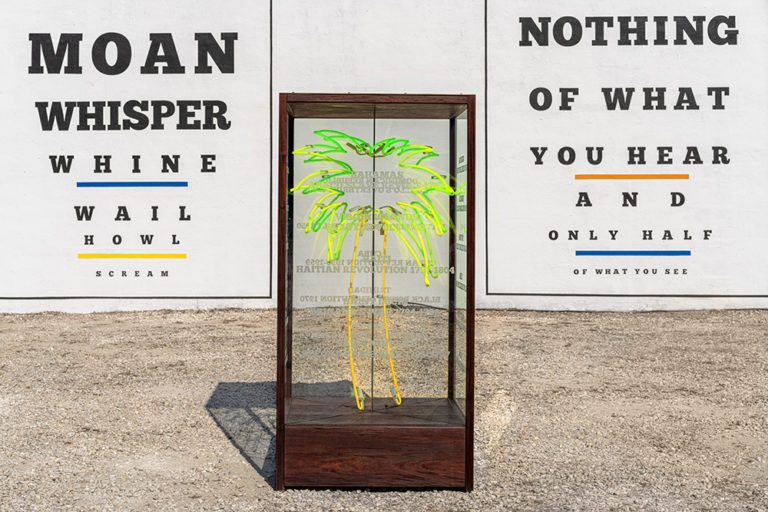

Fight for Your Land (2021) is the artist’s first public art piece in Florida. It sits in a vacant lot in Miami’s Design District, adjacent to the de la Cruz Collection and in the vicinity of other contemporary art world destinations. On a freestanding wall that demarcates the northern perimeter of the property, Navarro places four text-based posters, each as high as the wall and spaced evenly apart. Recalling eye charts, these word murals with letters of descending sizes put forward messages that evoke protest—indeed, the first in the grouping spells out “P-RO-TEST” across three rows. Perpendicular to these pieces is a lone neon sculpture of a palm tree, much smaller in scale so that it is nowhere near the height of an actual tree. The work sits encased in a vitrine elevated above the ground on a mirrored base. Simple in design, it is composed of two yellow lines that describe the trunk and green fronds that make up the crown and whose outlines resemble a cartoon explosion. Further emphasizing the schematic nature of the forms, two identical tree canopies are positioned perpendicularly to occupy three-dimensional space. The tropical sculpture recalls the neon signs of the midcentury roadside motels along Biscayne Boulevard, further establishing its connection to place and linking it to an earlier building boom. The glass that encases it contains text with a timeline. As opposed to the messages on the wall, the dates are unlikely to be read sequentially, given that they are placed at random intervals around the rectangular prism of the container. The years and places etched on its surface provide a chronology of rebellions and revolutions across the Caribbean into the continental space of the Americas, beginning with “Barbados / Slave Revolt 1633-1685” and ending with “Mexico / Zapatista Uprising 1994.”

One of Navarro’s earliest neon pieces also employed a timeline of sorts as a structuring device and referenced the state of Florida. In You Sit, You Die (2002), the artist created a folding sling chair whose armature was composed of neon bulbs and whose white cloth seat included the name of every person executed by the electric chair in the state from 1924 to 2001 along with the date of their death. That the names fill up the four columns of small text is astounding, revealing the Sunshine State’s dark and occluded history. Although most of the artist’s sculptures have clean lines and little evidence of wiring, this beach chair is hooked up to multiple cables, which converge in a metal box underneath. It is one of Navarro’s most ominous works. Here, as well, he addresses the viewer in the second person, voicing an impersonal warning.

The title “Fight for Your Land” recalls that of another public piece This Land Is Your Land, on view in New York City’s Madison Square Park in 2014. Characterized as an anti-monument, the work consisted of a series of large wooden structures resembling water towers atop platforms. Emanating light, when viewers stood below them, they could see words and, in one instance, a graphic. The messages included “ME/WE,” “ECHO,” and “HOBO” repeated into infinity through the use of mirrors, whereas the image was of a ladder extending eternally. The title of this piece is drawn from a Woody Guthrie song of 1940, which protested uneven distribution of resources in the United States at the waning of the Great Depression. It has also been seen as celebration of immigrant contributions to the country. While citing an anthem of equal opportunity and social justice, the message also evokes a paradox: the land across the American continent “belonged” originally to its Indigenous inhabitants. In Manhattan—or Manahatta, to use the Indigenous name—they were the Munsee Lenape. In Miami, the originary peoples were the Seminole.

The Miami installation urges the public to fight for “their” land in a space that is ripe for real estate development, a square patch of grass in an area that has fast become a concrete jungle. Alluding to the neighborhood’s growth and gentrification and their implications for the rapidly vanishing regional ecosystem, the lone palm tree not only resembles a cartoon, but it is encased in glass, like a relic needing to be preserved. That its fronds recall the imagery of an explosion ties into the timeline commemorating rebellions across the Caribbean, most of which were wrought by enslaved peoples. Beginning with Barbados, the artist references Jamaica’s First Maroon War (1655) and Tacky’s War (1760), St. Vincent’s First and Second Carib Wars (1769-73 and 1795-97), the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), and Cuba’s Ten Years War (1868-78), among others. Africans and Afro-descendant peoples in conditions of captivity could hardly be considered landowners under a capitalist world system, but the timeline provides a clue as to how the artist regards them as having a legitimate claim on land. Its final entry is the 1994 Zapatista Uprising in Chiapas, Mexico—Hach Winik territory of peoples also known as Lacandon Maya. This rebellion takes its name from Mexican agrarian leader Emiliano Zapata (1879-1919), who, along with Francisco (Pancho) Villa, was a major adversary of the Mexican state during the Mexican Revolution (1910-20). Zapata’s most famous dictum was la tierra es de quien la trabaja or “land belongs to those who labor it.” Through his work’s title, Navarro acknowledges a different understanding of landownership than one commonly held in the settler colonial, capitalist society that is the United States.

As a white Latino immigrant who remains deeply concerned with unfolding events in Chile and the rest of Latin America, Navarro is conscious that, not only is Chile also a settler society, but that it is considered to be the laboratory of neoliberalism, an ideology that advocates for free markets and deregulation as the way forward for modern nation-states. Neoliberal economic policies marked a continuity between the Pinochet regime and the transition to democracy. These produced a profound dissatisfaction as a result of growing perceptions of inequality and heightened social divides in the three decades following the fall of the dictatorship. In October 2019, a series of protests broke out across the country that became increasingly marked by violence. Yielding to public outrage, the Chilean president agreed to hold a referendum on whether to rewrite the constitution, which had been instituted by Pinochet in 1980. In October 2020, almost 80% of voters approved it.

These developments in Latin American geopolitics are very much at the heart of Navarro’s piece, for he is nothing if not conscious of the power of popular mobilization. The murals resembling eye charts that constitute the most visually impactful part of the project are a less-than-subliminal call to action. “PROTEST,” the first one instigates, while the last one urges, “RISE.” The charts are both a nod to the interconnection between conceptualism and politics in Latin American art, but also a subtle reference to the recent demonstrations in Chile. At the doctor’s office, eye charts are used by covering up one eye and reading out of the other. During the protests, over four hundred people sustained eye injuries from rubber bullets, leading to marches where people wore eye patches in protest. The eye charts in Fight for Your Land, then, are an affirmation of the potential of dissent.

The messages contained in the eye charts read as follows (with commas inserted for clarity, where appropriate):

- PROTEST, STREET, STRESS, OPPRESS, PROTESTER

- SIGH, MOAN, WHISPER, WHINE, WAIL, HOWL, SCREAM

- BELIEVE NOTHING OF WHAT YOU HEAR AND ONLY HALF OF WHAT YOU SEE

- RISE, REACT, REVOLT, REBEL, RESISTANCE, REVOLUTION, RENEGADE

In the first and last panels, the artist plays with words, riffing off variations on “protest” or else experimenting with alliteration by linking related words all beginning with R. The second chart starts with the imperative to sigh in huge letters and ends with “scream” in tiny ones, reversing the expectations of the words’ connotations in relation to their dimensions, while at the same time acknowledging that the need to protest often begins with something as mundane as exasperation. The third chart, which is the only complete sentence, humorously negates itself, undermining the senses of hearing and vision in the context of an eye exam.

These text pieces insert themselves into a tradition of South American conceptual art that often-used cryptic words and symbols to decry U.S. American intervention in Latin America or to protest the dictatorships that swept through the region from the 1960s to the 1980s. Antonio Dias’ 1968 Anywhere Is My Land—a title that recalls Navarro’s—superimposes a grid over a starry sky and prints the English-language title on the surface of the piece (the artist was Brazilian). The division of the space into quadrants alters the message from a potentially dreamy affirmation to a colonialist gesture fraught with violence. The Chilean Lotty Rosenfeld, a founder of the collective Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA), transformed lines on a deserted street in Santiago into crosses by placing white tape over them (1979). This simple gesture of reclaiming public space was a silent mode of resistance against the Pinochet regime, both an affirmation and an act of mourning. In 1983, CADA launched the celebrated NO+ campaign, which incited the public to finish the sentence “No more…” and imagine alternative futures. Alfredo Jaar’s A Logo for America (1987/restaged in 2014) inserted the negation “This is not America” over a map of the United States. Navarro follows in the footsteps of these and other artists, who marry the artistic and the political in unexpected and irreverent ways.

The bold letters of the charts contrast the subtle list of Caribbean rebellions, which are sandblasted on the glass that encases the palm tree. Navarro chooses events that in many cases are little known and celebrates acts of resistance and rebellion by Black and Indigenous people of the Americas. Arguably, the most famous occasion etched on the vitrine is “Haitian Revolution, 1791-1804.” It is, nonetheless, one whose scope and significance for hemispheric history and geopolitics cannot be overstated. According to a recent article by Howard French, “It’s one of the most remarkable stories of liberation that we have as a species: the largest revolt of enslaved people in human history, and the only one known to have produced a free state” (https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2021-10-10/the-west-owes-a-centuries-old-debt-to-haiti). Titled “The West Owes a Centuries-Old Debt to Haiti,” the story demonstrates how this extraordinary event produced a chain reaction in the Western Hemisphere that resulted in the transformation of the United States from a “vulnerable, coast-hugging collection of former English colonies to a continental power” through the Louisiana Purchase, or the sale of France’s North American holdings to the United States. In other words, the world as we know it would look very different had there been no revolution in Haiti. Indeed, it may have had an equal significance in world history as Columbus’ arrival in the Americas, but whereas the October 12 date of “Columbus” Day (renamed Indigenous Peoples Day or Día de la raza in some contexts) is widely known, few people are aware that the Haitian revolt began on August 21, 1791. I have argued in other writings that “Latin” America has deliberately constructed itself in opposition to Haiti, isolating it while defining its own identity in the image of the West and as a European diaspora. Regional projects of mestizaje, or racial mixing, and blanqueamiento, or the encouraging of European migration, sought to whiten local populations, assimilating Indigenous people and erasing the stain of slavery and with it the Afro-descendant populations of any given country and especially those along the Pacific coast, from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego. As such, Latin America as a regional construct is predicated on “white normativity,” or what African American philosopher Charles W. Mills has described as “the centering of the Euro and later Euro-American group as the constitutive norm” (C. W. Mills, “White Ignorance,” in S. Sullivan and N. Tuana, eds., Race and Epistemologies of Ignorance, Albany: SUNY Press, 2007, 25).

By evoking Black and Indigenous acts of rebellion, Navarro recognizes that these histories are intertwined with those of white and mestize settlers like himself. Black Latin Americans are a demographic that is frequently erased in national imaginaries and hemispheric histories—the delineation of the non-hispanophone Caribbean as a separate region from Latin America is part of this tendency. Indigenous people, meanwhile, cannot be divorced from the continental territories they continue to inhabit. Rather than regarding them as historical agents, however, they are popularly seen both as passive and submissive and as a vanishing minority. In acknowledgement of the obscured pasts of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples of the Americas, Navarro’s timeline could not be more understated; he nonetheless highlights their heroic achievements for those who wish to broaden their knowledge and challenge the “epistemologies of ignorance” that Mills sees as characteristic of white supremacy. In a Miami urban site marked by continuous displacement of first the Seminole and later the impoverished communities who lived in nearby neighborhoods, Navarro calls attention to the violent history of the Americas as one of both dispossession and rebellion. But he also reveals how erasure is enacted through reoccupation. Their land became our land, and it is only by looking for what most people will ignore that we not only begin to see, but we also become aware of our own complicity.

Iván Navarro has been working with neon light as his primary medium over the past two decades. Born in Santiago, Chile in 197, just prior to the advent of the military coup. His move to New York in 1997 determined the direction of his art, but Chile has always remained close to his heart and mind. Although Navarro’s light sculptures tend to dazzle the eye and evoke multiple associations—ranging from spirituality to commerce and technology—the work is always political.

–Tatiana Flores, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey